The Navigator provides insight into stock market events with an outlook.

October 5, 2021

“Wave breaker”. With rising inflation, the markets are stalling. The markets are also taking back some control, while the central banks are trying to keep the yield curve under control. Whether interest rates continue to rise in the trend or not, both could lead to a decline in credit creation. If interest rates rise, it will become uncomfortable for many debtors; if interest rates fall, the “margin of error” for credit-creating banks shrinks and loans are granted more selectively. Waves break when the height reaches 1/7 of the length. Mountains of debt also build up and are reduced in one way or another. Whether we are close to such an event remains to be seen.

Market review

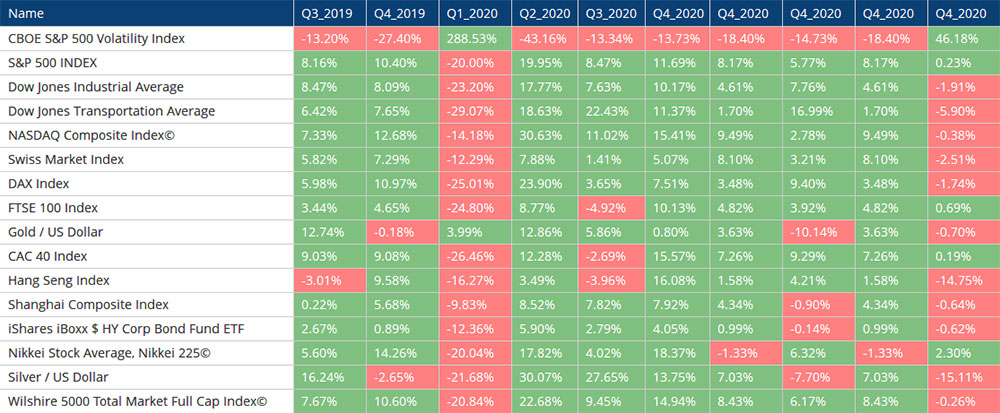

The third quarter continued, in a way, what the second quarter started: The consolidation continues. So much for the superficial events, read from the price development, in shares, but also in raw materials or, in the big picture, in interest rates. Inflation is on everyone’s lips among market commentators and the view has become established, to a certain extent, that the price increases are not only of a short-term nature. After the reopening of large parts of the global economy, which led to interrupted supply chains and reduced capacities due to forced closures, the price increase of many products, components and services should only be of a temporary nature – until everything is up and running again.

After the stock markets tended to leave the second quarter rather at the upper end of the range, the third quarter was left tending to the lower end of the range. This was mainly due to the last third of the quarter, or the last week in September. A mixture of fundamental data from the economy, developments in the Covid figures – also in connection with the vaccinations, plus the dire news from China regarding Evergrande, urged many investors to be cautious. As a result, the Chinese markets suffered the most. If you scratch the surface of the presented and impressive growth figures in China, some are almost overcome by naked shudders: External financing to an extent that we (still) do not know in the West. Over 150% debt for companies, compared to 80% in the USA, for example. With all the uncertainties, the joy of fluctuation increased, as the increased volatility index also shows.

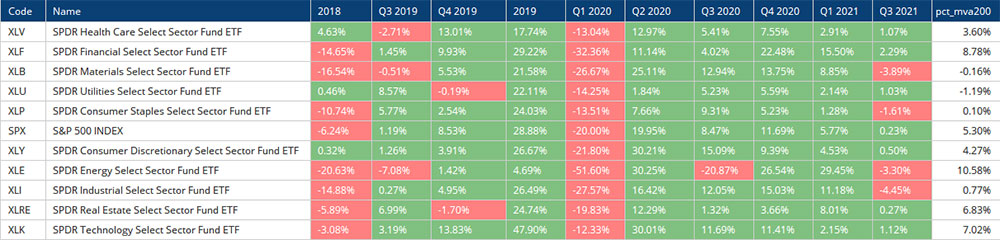

There were relatively small differences in the sectors: All have come out of the 3rd quarter relatively unchanged in one or another pronounced form. The manufacturing sectors, such as industry, continued to suffer from the supply chains that were not yet intact. The financial sector, for once, benefited from the slightly steeper – with the prospect of becoming even steeper – yield curve.

The Evergrande crisis shows that even in times when Modern Monetary Theory is being propagated, a kind of physical law also exists in the financial sector: Debts must either be refinanced (which also requires sufficient liquidity) or repaid. Otherwise, bankruptcy threatens with losses for the creditors. Or, the debts are inflated away.

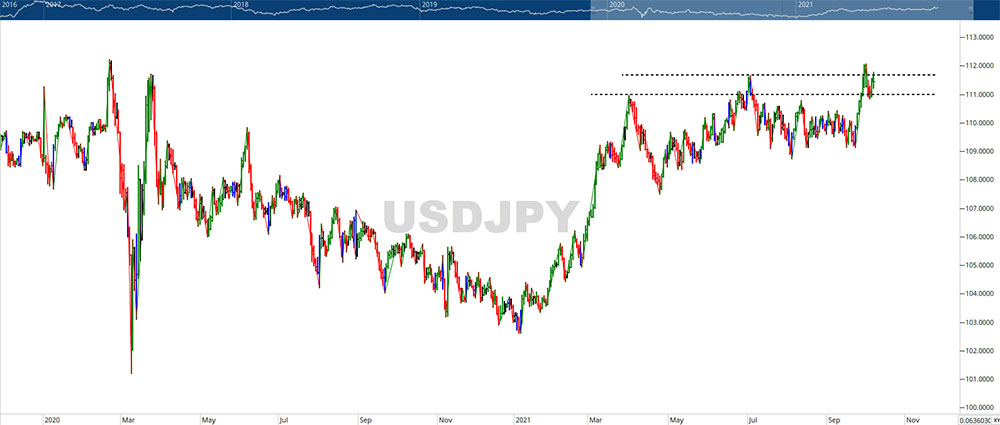

A stronger USD was seen in currencies and commodities, including against the yen. From the perspective of the flow of money from the large currency pools, a weak yen (carry trade) suggests intact investment activities, i.e. confidence does not seem to be greatly damaged.

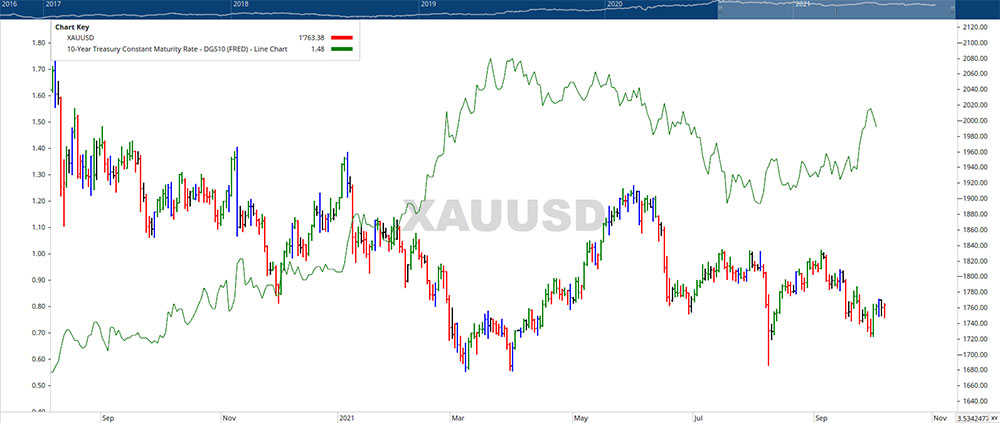

With gold, one could say that the negative correlation with the development of interest rates was again evident. However, gold is also known as an opaque market with a temporary life of its own. You simply have it in the safe or in the portfolio, as a kind of insurance or calming pill – because ultimately it has always proven its value.

In the area of cryptocurrencies – which has been perceived as a new asset class by well-known investors for about a year – there was another breakout upwards, contrary to the general trend. More than that, in addition to the now well-known coins such as Bitcoin or Ether/Ethereum, NFTs (non fungible token) were a topic. In principle, this is a kind of “smart contract”, i.e. a protocol that can do certain things. For example, you can save a specific image and then save this image file on the blockchain via NFT. Such images can then also bring rights with them, such as a club membership, etc. We believe that this still young story is a kind of “honeymoon” phase: one is fascinated by the new, and as if one falls in love, one sees only rosy red (one knows nothing yet about the mother-in-law and other possible challenges). Also, a lot of money has been earned in the area of cryptocurrencies, which means that the participants have a lot of money at their disposal and spend it accordingly, perhaps also somewhat uncritically. Nevertheless, the story is not entirely worthless, the question that arises is probably much more: where is the value, where is the price too high?

In focus

The Evergrande debacle brings this to mind again. After great confidence in the Chinese growth story, the other side of the coin is being shown for once: The excessive growth within a relatively short time could only be bought due to – as we now see again – relatively high debt. This tendency is also evident in the West, but thanks to our structures with a more or less free market and so-called “checks and balances”, we are still somewhat better off. But we are moving in the same direction. The question is when and how the situation will be resolved. Will it happen through higher interest rates, e.g. if inflation picks up and it becomes more difficult to refinance? Or will interest rates slide back towards zero or below, making it more difficult to generate enough income to pay off the debt burden? Some believe that we are currently on the way to some inflation with weak growth. Then the savers, the middle class without large ownership of assets, pay. This in turn is likely to lead to social tensions and political upheavals. We see it similarly to Robert Heinlein: TANSTAAFL (“there ain’t no such thing as a free lunch”).

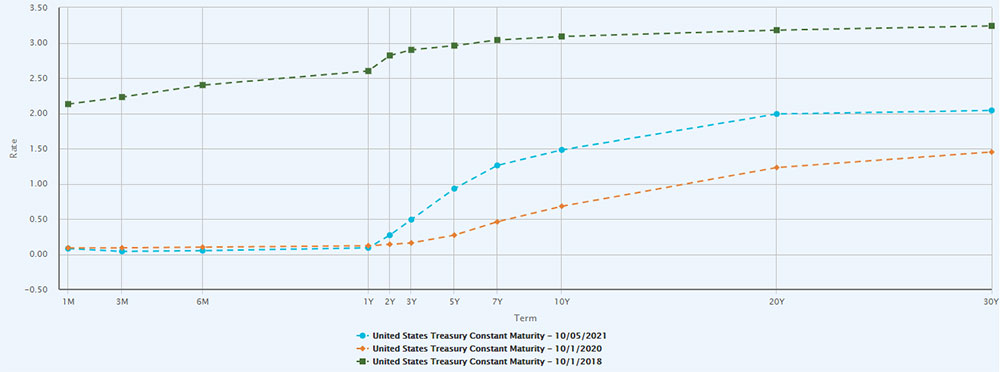

In terms of inflation, the current situation is reminiscent of the 1970s – even though much is different today (back then, the post-war generation, the baby boomers, entered the workforce; today, the same are retiring and the next large generation, the millennials, is smaller). But: When inflation measured by the CPI stood at 5.3% in 1973, the US Federal Fund interest rates were at 6.75% (the USD corrected sharply against gold at that time). The US Fed then predicted a temporary flare-up of inflation, also due to the unemployment statistics, which at that time was around 5% with a positive outlook towards 4%. Consequently, inflation should come to lie at 4% – according to the models. It turned out differently. In October 1973, the oil shock, the supply shock of that time, happened. About two years later, in 1975, inflation measured by the CPI was around 10%. The unemployment rate at 9%.

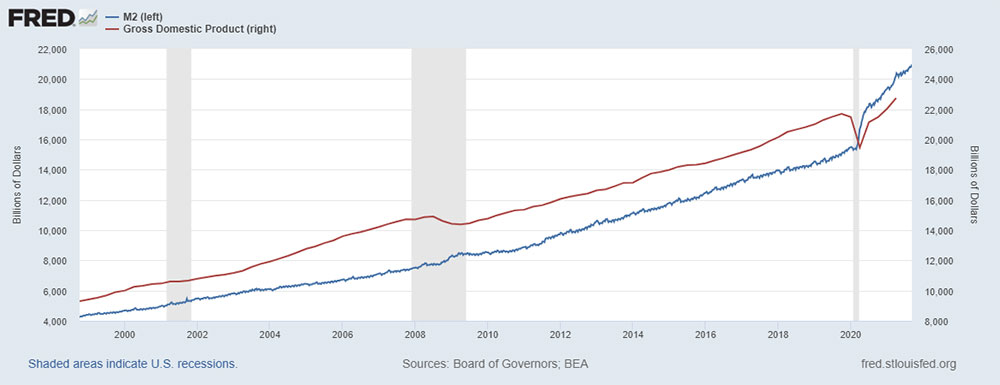

Of course, much was different back then. However, there are also certain parallels with the supply shock and a central bank that is academically oriented and perhaps relies too much on its models. There is also a rapid expansion of the money supply. Measured by M2 – cash plus sight deposits and savings deposits, money market fund shares and other term deposits – the expansion with the stimulus money distributed by the governments has reached a new dimension.

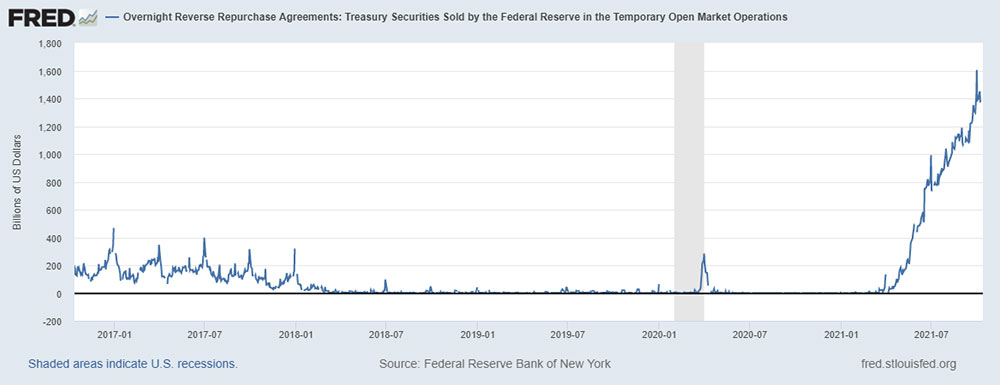

At the same time, the central bank (US Fed) absorbs the superfluous liquidity via securities sales to commercial banks. The money is not invested in the economy, but is virtually returned to the central bank (overnight, at a low interest rate).

The showdown between inflationary and dis-inflationary or even deflationary forces could well go into the next round. However, the situation is escalating further until we either have a devaluation of money or write-offs on the debts. The wave breaks, the piled-up mountain of debt collapses (or the air escapes the balloon).

Outlook

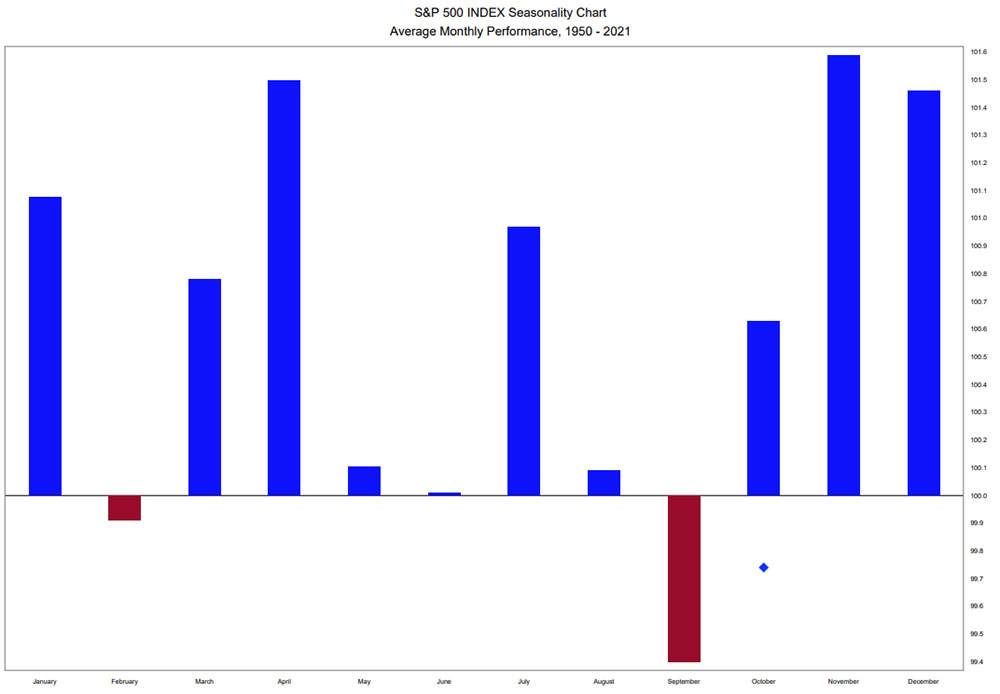

October is considered a difficult stock market month, as the crash of 1929 and 1987 happened in this month, as did the mini-crash of 1989 with the beginning of the first Gulf War or with the Asian crisis of 1997. However, statistically speaking, September is the weakest month for the stock markets.

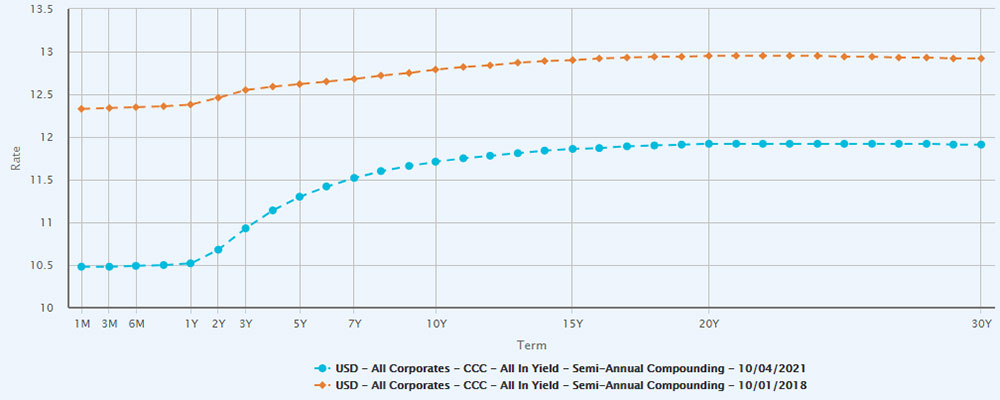

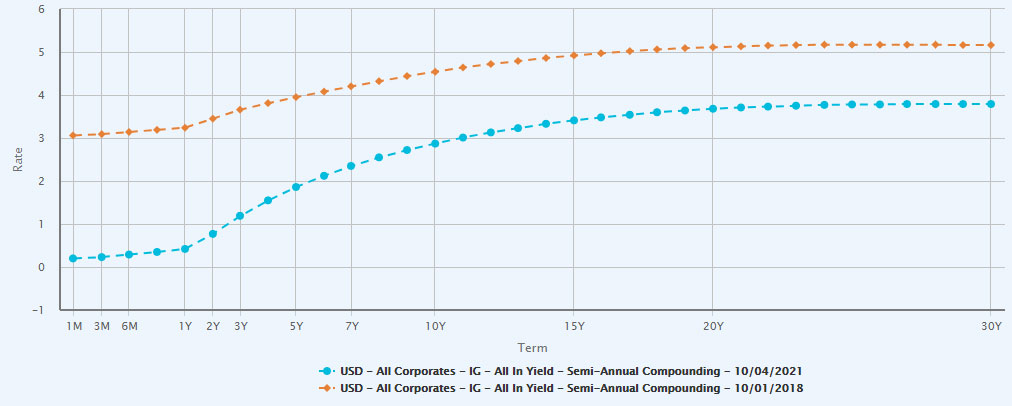

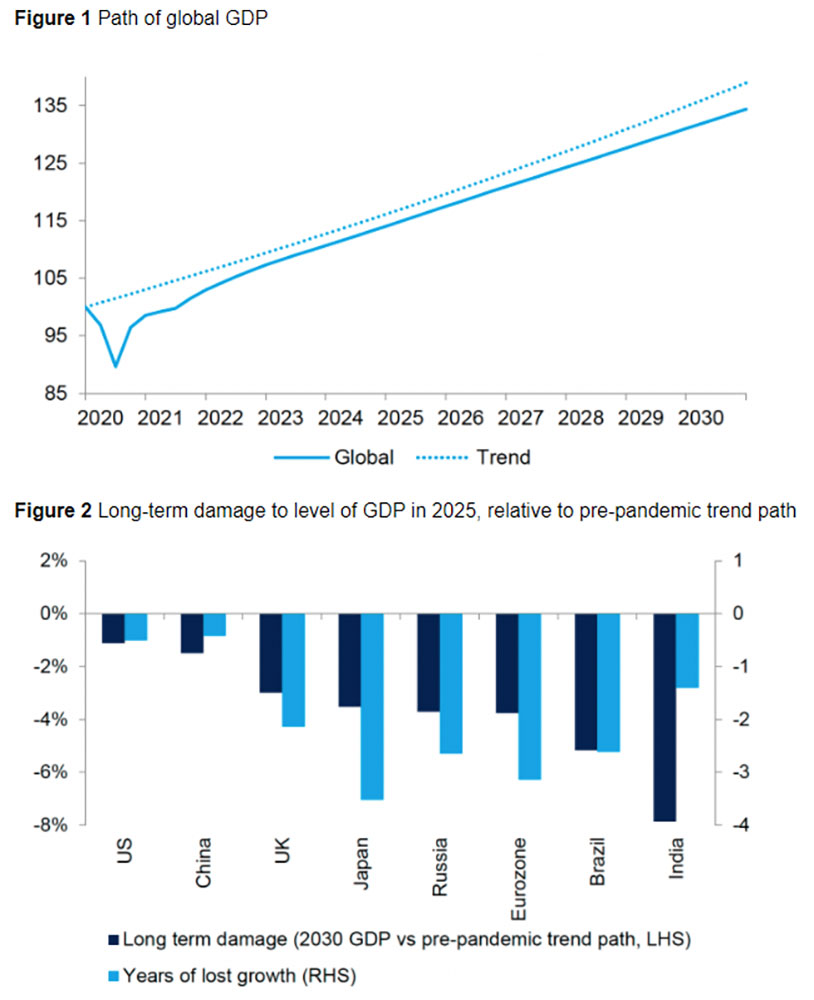

The correction initiated in September of this year is the longest lasting in terms of the number of days since the virus crash in March 2020. However, measured by the price loss, everything is (still) within limits. Although important support lines have been approached or even undercut at the end of the quarter – or at least scratched (intraday), it will first have to be seen in October whether it will become a – yet again – bad or even terrible month. The upcoming economic data will again provide a few more splashes of color so that one can paint a better picture. The crucial question remains: Are we seeing a correction or a trend reversal? The future remains uncertain, but scenarios can be imagined. In our opinion, the main drivers of the stock market boom remain: Money is cheap to have, interest rates are low, there is a shortage of investments. If the interest rate turnaround picks up speed and interest rates rise towards the levels of October 2018, a regime change could become apparent at the latest then. Currently, it remains to be seen how the situation develops on the supply side of the economy, or then also on the demand side. Depending on how the Covid situation will develop. Economists from Aberdeen Standard Investment estimate the damage caused by the Covid situation at over 3% of global economic output in the long term.

With the slowed growth and rising inflation, the scenario of stagflation is again making the rounds. The central banks do not seem to be able to do much anymore. There are also already voices calling for not buying up bonds at the long end of the yield curve anymore. Because the low interest rates disadvantage the wage earners, who do not benefit from the increase in value of the assets, and are dependent on interest income for retirement provision. Whether the situation is already ripe enough for a trend reversal is still open for us. However, we fear that with the passage of time, a turnaround will become increasingly likely. Similar to a wave that builds up and then collapses again.

“It is better to be approximately right than precisely wrong.” Warren Buffett

EDURAN AG

Thomas Dubach